Text by Kori Udovički, published in NIN on 18/11/2021 (translated from Serbian)

It has become completely clear today that development priorities are just not a political priority. Economic growth is not the same as development. There are rich countries with poor peoples

Serbia shows no actual progress in this year’s European Commission’s Progress Report on its readiness for EU membership, just as it didn’t in previous years. The report clearly indicates what has, and what has not been done. The authorities declared it “the best report in the last few years” because the text has a slightly more positive tone overall and in its assessments in the umbrella observations. The term “state capture”, which was present last year (for the first time), does not appear again. Efforts are evident to “give points” to Serbia for progress such as, for example, that the number of laws passed by urgent procedure has declined, although the speed of the procedure in a parliament with no opposition is irrelevant. Maybe Europe was worried that it would push Serbia too far away from itself. Or maybe someone judged that, together the facts that the proposed constitutional changes on the judiciary are indeed an improvement and that Serbia is at least confronting one of its organized crime clans, prevail over the fact that this confrontation has clearly revealed how inseparable crime is from government structures and that the latter will not at all be brought to account. Finally, the European portal Politico states advances the thesis that the report was embellished at the last moment by Commissioner Varhelji, close to the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. The answer is, most likely, “a little bit of everything”.

The economy is growing

There is also little doubt that Serbia’s very solid economic performance, for a second time in a row, contributed to the positive tone of the Report. Serbia’s growth was one of the highest in Europe, and this enabled Serbia to increase budget spending without a significant increase in public debt, now possibly even declining again in percent of GDP. Certainly, a disregard for the health situation “helped” economic growth (at the cost of human lives) Serbia is, along with Bulgaria, the “leader” in excess mortality during the pandemic. It was also helped by a strong fiscal stimulus for which, it is important to recognize, the space was created with the fiscal consolidation a few years ago. However, the extent of the resilience shown by the Serbian economy in the pandemic indicates that something more has been at play. The question is – what could it be? The report itself points to a large number of institutional weaknesses that have not been corrected over the years. In fact, we as citizens see institutions being devastated. Does this mean that a “favorable business environment”, which of course includes the quality of institutions and the rule of law, is not important for economic growth? Or that the business environment has somehow improved?

The answer is that the Serbian economy is growing despite the weakening of institutions, due to a favorable set of structural, even historical, circumstances. In fact, Serbia is missing a unique opportunity to go beyond a temporary acceleration of growth, and start developing rapidly, closing the socio-economic gap with countries of the European Union. After almost two decades of slow and painful economic transformation, Serbia entered the pandemic with a healthy base of dynamic economic entities. That transformation, through the cumulative reforms that accompanied it, the recent stagnation of wages, and, simply just the passage of time, helped Serbia become more competitive at a time when the global economic scene is restructuring. The fiscal consolidation and then-initiated public administration reforms opened the opportunity for increased and better-targeted public investment necessary to support development. That fiscal space is now being wasted, and current industrial policies, as well as the way in which they are implemented, reduce the level and quality of investments, especially those that can contribute the most to the well-being of citizens. Let’s look at these in turn.

There is no doubt that economic growth in Serbia is currently being driven mainly by foreign direct investment (FDI). This is, as the Report emphasizes, good for macroeconomic stability. It is also good that Serbia attracts part of this FDI because of the aforementioned restructuring of global value chains. Capital is returning from Asia to Europe, and is increasingly moving from Germany as well. As China and the CEE have moved up the ladder of development in the past two decades, Serbia can now “win over” the more labor-intensive projects. These are investments in manufacturing which are moved by an expectations of increasing production capacity and exports. They, hence, bring economic growth not only while the investment lasts but, as a rule, after it as well.

Structures are being built but– what kind?

The problem is that a large part of the significant increase in FDI recorded by our statistics does not concern the opening of factories, which is what we usually have in mind by FDI. The increase in average annual FDI into manufacturing (€ 200 million) is only a small part of the total increase in FDI (€ 1.7 billion) in the past five years. The lion’s share of that significant increase (1.1 billion euros) actually refers to flows into „land transport and piplines“ or into the real estate and construction sectors sectors. In the first case, the figures clearly correspond to the value of the gas pipeline, actually a public infrastructure project that is treated as FDI because it is run by a (publicly owned) company. In the second case, the flows are almost certainly into development of real estate, mostly in Belgrade. In both cases, of course, these are investments whose contribution to the country’s production capacity is far less “assured”. The rest of the increase in FDI flows refers to the Bor mine and steel and copper production, which will raise productive capacity but with questionable environmental containment efforts.

Also the structure of investments in the manufacturing industry itself is not optimal. Methods of attracting them still give a significant advantage to projects with a large number of low-skilled employees (in the thousands), although unemployment is no longer the only, and perhaps not even the main, development priority. The problem is really not in that such projects rely on lower paid labor but that they offer this labor and entrepreneurs in their environment fewer development prospects. These are huge systems in which simple products are mass-produced. Making such products do not offer workers much learning opportunities, and many also do not offer opportunities for adding complexity later. Finally, they do not offer Serbia an opportunity to supply much. Another problem is that manufacturing investment attraction is focused on only two sources: Germany and China. While with Germany a positive feedback loop has been created based on good mutual experiences, largely thanks to consistent German official assistance, from China we are attracting polluters that China wants to get rid of, and into places such as Zrenjanin where it was certainly possible to invest in many better things.

Actually the experience with Germany, from where we are increasingly attracting higher-quality investments, shows how opportunities opened with the consistent investment in people, connections, reputation and cooperation. This is how institutions are built under normal conditions. The problem in our case is that this is effort is not carried out only, nor even mainly, by institutions, but by the completely centralized parallel structure built around the office of the President. Thus, the experience cannot spread and expand to a larger number of sources, nor to a larger number of smaller and finer projects. The persistent focus on large projects and on only two countries of origin have the same explanation – the limited capacity of one center from which everything is run.

The domestic economy – a neglected potential

It would be desirable, and this is now realistically possible, for a much larger part of the growth to be driven by the domestic private economy itself – through its own investments. After almost three decades of painstaking development, this economy has matured. The ease with which it overcame the state of emergency, and even the shocks that followed, indicates that it has significant reserves. Its maturation took place in parallel with the transformation, to a large extent extinction, of the “traditional” economy inherited from socialism. The transforming traditional economy fed the new domestic economy with resources, but also burdened it with its poor performance, non-payment of bills and the burden of taxes used to subsidize it.

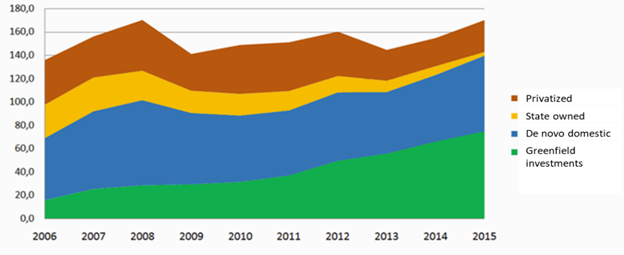

The process of building a new domestic and foreign-owned economy and the parallel process of transforming the traditional socialist economy can be illustrated by a particularly vivid example of the machinery and electrical equipment sector, and also through the export of goods. The first chart shows revenues by company ownership in the machinery and electrical equipment sector. Revenues of newly established domestically owned companies (marked in blue) increased by around 25 billion dinars from 2006 to 2015, revenues of brand new (greenfield) FDI (green) increased twice as much, while revenues of companies that were once was state-owned (and in 2015 or other state-owned, marked in yellow, or already privatized, brown) decreased by about 40 billion.

Machinery and electrical equipment sector: revenues, 2006-2015

RSD 2015

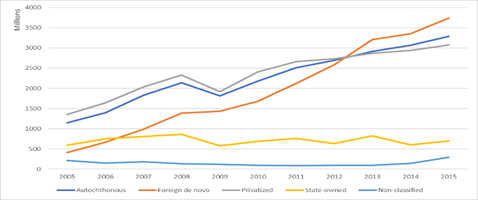

Similarly, the dynamism of the new domestic economy can be seen in the structure of Serbian merchandise exports by ownership of exporters (colors are somewhat different compared to the previous chart). The new domestic economy is fully keeping pace with the rapid growth of exports of privatized companies (excluding Fiat and Zelezara) suffering a decline only in 2009. This is impressive, because most privatized companies are in the hands of foreign owners with much better access to capital and export markets than ours.

Serbia’s merchandise exports ownership of exporter company, 2005-2015 in mill. EUR

(Fiat and Steelmill Smederevo are not included in the calculations)

Today, when the transformation of the traditional economy and fiscal consolidation are over, when it is evident that SMEs have reserves, and when finally the government is spending significant amounts- we should see an increase in domestic company investment and not only foreign ones. While precise data are not available, available data suggests this is not the case.

A very unequal playing ground

The performance of the domestic economy continues to be burdened – by the weak economic environment. In this regard, the EC Report could be criticized for the assessment that in the observed period (June 2020-June 2021) the economic environment improved slightly. That was true a few years ago, but now it would mean that very few regulatory changes and a bit of procedure digitalization took precedence over the increasingly visible absence of the rule of law (especially confirmed through public discourse on organized crime). We cannot measure this effect, but there is no doubt that clientelist management of public enterprises, corruption and the absence of the rule of law play a significant role in “cooling” domestic investment passions.

The domestic economy does not receive the same attention, nor funds, dedicated to FDIs. As the Report notes, SMEs face an “unequal playing field because they do not have direct access to the government as do large companies and foreign investors”. (By European standards, just about the entire domestic economy is SMEs). While insider large companies and FDIs can speed up administrative decisions with this direct access, the implication is that small ones will therefore have to wait even longer. An additional problem is that FDI is attracted with incentives that are not adapted to the characteristics (mainly dimensions) of domestic companies that therefore generally have no access to it, while funds dedicated to SMEs are severalfold smaller, and fragmented. Finally, the domestic economy is not consulted in the decision-making about which FDI to incentivize, and where. While the spending of an FDI will generally give an impetus to local economic activity and employment, it can, if not carefully planned, endanger those (fewer) local SMEs with more a substantial growth potential. This will happen primarily through competition for staff and other resources. What is there to be gained by encouraging foreign and not domestic investors in the production of chocolate or furniture?

The way in which the government manages the spending of public funds, especially investments, does not help increase private investments and growth, and more importantly – the effect they can have in the future. Let’s start with the example of the subsidies to the economy during the pandemic crisis. The space created by fiscal consolidation enabled strong spending, and this provided an impetus to growth. However, as has been pointed out many times in public (and recognized in the Report), it was not targeted at the most vulnerable households and businesses. Had it been, it would have produced higher economic growth and higher investments, as the same help to those more in need – be it poor citizens or affected companies — makes a much bigger difference in their behavior than helping those doing well anyway.

Shooting from the hip

It has never been more important to think through priorities for the direction of public funds, especially medium-term national investments, nor has the absence of such analysis been less justified. From 2017 until today, investments in transport and energy infrastructure have significantly increased and will continue to increase – without an expert, not to mention participatory, process to answer the questions — what types, how much, in what locations? Do we really need whole new highways to meet the development needs of some parts of Serbia, or would it have been better to build only a third lane (for the time being) and invest the savings in other needs? Highways and railways will require maintenance in the future – where from will these resources come if they happen not to result in a commensurate increase in production capacity? And how will they result in a commensurate increase in productive capacity if the small companies that should thrive due to their proximity are presently reduced to (in vain) roaming backstage inquiring if there will be get a connector from their place to the highway?

Not only has this analysis not been done, but there is no document, not even a note, which all potential investors could consult, to learn about the plans that before the last elections were called the “Serbia 2025 Investment Plan”, and that are etched, apparently, solely in the President of the Republic’s mind. The EC has been not only waiting, but actually endeavoring to help, the implementation of its year-after-year repeated recommendation that Serbia “establish a single, comprehensive and transparent system for planning and managing capital investments.” The question of investment prioritization was posed to the Prime Minister at the Plenary Session of the National Convention for the EU. She replied, referring to the environmental sector, that “there is no priority because it is about extinguishing fires.” Such an explanation could have been acceptable at the beginning of the 2000s, and even at the beginning of Vučić’s rule, as a planning system had not been built in the meantime. Today, however, it is quite clear that development priorities are simply not a political priority. Economic growth is not the same as development. There are also rich countries with poor people.

The European Commission’s report does as much as it can– it even recognizes that the weakness of institutions threatens the sustainability of economic growth. But the process of joining the European Union is not adapted to situations in which someone is not interested in real progress. The fact that Serbia is missing a historic chance for development is, above all, a question and a task for us – the entrepreneurs and citizens of Serbia.

By Kori Udovički

The text is a translation of an Op-Ed published in NINu 18/11/2021; it includes a correction with regard to the composition of FDI.

SR

SR