News

(SR) Konkurentnost privrede Srbije – „Skok u budućnost“ ili u ekonomsku stagnaciju?

In the Shadow of the Canopy: The Shaky Foundations of Serbian Economic Growth

Protests certainly weren’t the main culprit for the slowdown in economic growth in the first quarter of this year, but they exposed the fact that Serbia’s economic growth in recent years has been resting on increasingly weak foundations.

President Vučić was blaming protests for “scaring away investors and tourists” even before the data was released. It turns out that the protests indeed scared one investor – the state itself, because, in the President’s own words: “Now there isn’t a mother’s son who will sign any paper.” This is evident in government capital expenditures which, in the first quarter of the year – a quarter when acceleration of expenditures was expected primarily for Expo-related projects – actually fell by 3.7% in nominal terms, and by as much as 7.8% in real terms. Rapid government investments have served until now to maintain economic growth even as export growth slowed. It seems that President Vučić has finally exhausted the quick methods of boosting economic growth.

Growth Structure and Changes in FDI

According to flash projections from the Statistical Office, GDP growth in the first quarter of this year compared to the first quarter of last year fell to 2.0%, versus expectations of 3.5%. These expectations took into account the exceptionally high base in the first quarter of 2023, while 4% was expected for the whole of 2025. The key contributor to this underperformance was the slowdown in public investments. There was also a slowdown in the inflow of foreign capital, which halved compared to the exceptionally high inflow in the first quarter of last year.

Serbia’s solid economic growth over the past years has so far been primarily associated with strong FDI inflows. Serbia stood out because, in the period from the pandemic to the end of 2024, these remained relatively high and stable (growing from €3.8 billion in 2020 to €5.2 billion in 2024). However, FDI is not a homogeneous category. During the observed period, their composition and perspective of contribution to sustainable development of the country changed significantly.

Frequent ribbon-cutting ceremonies in front of new, foreign, mostly German factories have accustomed the Serbian public to equate foreign investments with investments in manufacturing. These were primarily aimed at creating as many jobs as possible, which was indeed a priority at the beginning of this regime. FDI in export-oriented manufacturing appears beneficial also because it typically brings knowledge, technology, and generates foreign currency inflows. However, investments in manufacturing are just one component of FDI. They made up only 38% of the total in 2021 when they reached their peak in real terms (€1.5 billion). Since then, they have been declining, so that in 2024 they amounted to only €0.6 billion (11% of the total).

Since 2021, only FDI in mining has been growing steadily – doubling in each of the past two years, reaching €1.4 billion in 2024. Production and exports of ore and copper concentrates have also grown, which undoubtedly contributed to the overall measured GDP growth. However, given the lack of transparency in exploitation conditions, assessing the actual effect of this project on growth and development, especially compared to what might have been possible, would require a separate study. In any case, we have no doubt that this represents a missed opportunity. While copper prices on the global market are booming, with prospects for further long-term growth, Serbia’s mining royalties and negotiating power with China are low.

The largest component of FDI in 2024 (€1.5 billion) consisted of investments in the construction and real estate sector, whose contribution to GDP growth, and especially to foreign currency inflows after the investment period, is most questionable. Their actual amount is also questionable. On one hand, it is possible that in some cases, government borrowing through bilateral credit arrangements is first reflected in statistics as capital inflow from construction companies from the respective country, and only later as the Republic of Serbia’s debt. In that case, we’re not talking about an inflow of private, market-driven capital, but about Serbia’s public funds. It’s also likely that, in the context of corrupt activities, part of this money consists of “laundered” domestic capital, especially since the counterpart to this large item in the structure by country can mainly be seen in inflows from tax havens.

Exports – Crises and Opportunities

The trend in goods exports, especially manufacturing products, follows the described investment flows and has been contributing less and less to economic growth for some time. Since the reversal in the structure of FDI flows, its real growth has been halving in both 2023 and 2024, while in the first quarter of 2025 it even decreases in real terms, despite the growth in exports of ores and non-ferrous metals. The main “culprits” are, of course, difficulties in the European economy, primarily Germany. These have especially affected the part of Serbian exports included in the global value chains of the automotive and related industries, as well as those industries that rely most heavily on cheap labor. This has undoubtedly been contributed to by the fast growth of the “lowest” wages alongside the appreciation of the dinar.

Thus, during 2024, we witnessed a reduction in the number of employees in a significant number of foreign factories – for example, Yura, Mei Ta, as well as the closure of others – Adient, Siting (closed its facility). The decline in exports of these products in the first quarter of 2025 accelerated to €430 million, almost as much as in the entire 2024.

It’s clear that these investors aren’t packing up because of protests, but rather due to a longer-term and deliberate process. Even as such, their departure is relatively quick because the investors who are leaving are those who came with the least capital investment and the least prospect of their own development, easily attracted by subsidies or political agreements.

On the other hand, there are two positive stories in exports. One is the strong growth in service exports – especially ICT (nominally 17% in the first quarter of 2025) – which is in line with the positive trend in FDI inflows to this sector. This inflow, we must emphasize, could only have been encouraged by the protests. But IT services are also exported by domestic companies, which is in line with the second piece of good news. That is the continued growth in goods exports from sectors where Serbian producers are predominantly present – food, metal, plastics industry, wood (furniture and other machinery have been declining lately).

From conversations with these entrepreneurs, we learn that they are managing in conditions of slow European demand by offering competitive goods when European companies are looking for savings, or by turning to markets of former “third world” countries. They are also doing well in the wider region. Of course, this represents a missed opportunity, because domestic production and exports are not only inadequately supported but are discriminated against by tax and subsidy policies, and weak export support that puts them at a disadvantage compared to the competition.

Mortar in Exchange for Exports

It is important that during this period, public investments replaced goods exports as the engine of economic growth. Government investments in 2021 reached 7% of GDP and have since grown fast enough to maintain and even raise that level in 2024. This would be quite alright if it served to raise the productivity of the domestic economy, especially for people with the lowest wages – if their education and on-the-job training were improved, if they were prepared for more complex jobs, or if the infrastructure that foreign factories are abandoning was prepared, with appropriate programs, for domestic SMEs that are desperate for industrial locations.

Investment in road infrastructure was certainly productive in earlier years, when investments filled obvious, urgent needs, and with less haste. However, in recent years, the selection of investment projects has been done without clear criteria, consists of too much cement, not to say mortar, and too little equipment, and it is done at the expense of investing in the state’s capacity to provide adequate support and development services to the economy and citizens.

The collapse of the Novi Sad railway station canopy is not an isolated incident, just as the accident at TENT 3.5 years ago was not an isolated incident, but the tip of the iceberg of delayed or poorly executed investments in EPS and other public enterprises.

Conclusion

For President Vučić, the slowdown in government investments represents a huge problem. Not only does it increase the risk of missing deadlines for the Expo, but, as we have shown here – the key (short-term) driver of economic growth is being lost. And this is happening precisely at a moment when, under conditions of political crisis, the President especially needs to produce results. According to public statements, the President still believes that the lost time can be made up.

For citizens, the problem is that the political elite blames protests for problems it is unable to solve. It is unable to raise the productivity of the economy through investments, because that requires dialogue with it; it is unable to lead them quickly and responsibly, because that requires competent and motivated civil servants. It is unable to see, let alone activate, the potential that lies in the domestic economy – because this requires fair market competition, and again – competent and motivated civil servants, as well as productive and service-oriented public enterprises. It is unable to seize better opportunities that are still opening up in the restructuring European economy – because that requires the work of an entire network of people and competent and motivated civil servants.

In any case, it is better for citizens that economic growth slows down than for some “mother’s sons” to give in under pressure again.

Author: Kori Udovički, Chairwoman of the Board, Director, CEVES

CEVES Newsletter – The shaky foundations of Serbia’s growth; Is Serbian economy suffering from Dutch disease?

We share with you our newsletter for the first quarter of 2025 – which, in addition to a brief overview of the most important economic trends in Serbia and the EU, also provides our reflections on the key challenges shaping the economic and political climate, as well as CEVES’ activities during this period.

The past quarter saw Serbia’s economy slow its growth, with global economic policy uncertainties and possibly a domestic political crisis beginning to spill over into economic sentiment. In the “CEVES Perspective” section, we address signs that institutional weaknesses (rather than protests) have started visibly hindering economic growth (unlike sustainable development, which they have been obstructing for some time).

According to flash estimates, Serbia’s GDP growth significantly slowed in Q1 2025 (2% vs. 3.9% in 2024), primarily due to a continued slowdown in both public and private investments that began in the second half of 2024, as well as a further decline in goods exports to Western markets. Although direct data is not yet available, this is inferred from a sharp decline (-55%) in foreign direct investments in the first quarter of this year and a drop in the state’s capital expenditures (-8%) throughout the quarter compared to the same period last year. The value of exports of ICT and other creative services, as well as ores and base metals, continued the strong growth from the previous period, likely explaining why growth still remained positive.

Change in the export structure is reflected in the growth of exports from the mining and base metals sectors (+16%), alongside a simultaneous decline in exports from industries involved in global value chains, such as the automotive industry and related sectors, as well as those relying on low labor costs (-20%). Service exports, led by ICT, recorded real growth and made a significant positive contribution. Domestic consumption remained the only stable component: public consumption grew slightly in real terms, while private consumption likely began to weaken, as indicated by a decline in domestic tourist overnight stays, lower VAT collection, and stagnation in retail.

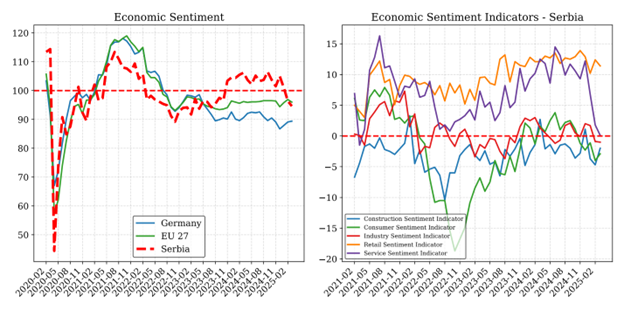

Economic sentiment in Serbia at the beginning of 2025 fell below 100, aligning with the EU27 average, primarily due to a sharp decline in sentiment in the services sector – one of the lowest since the pandemic (although, unlike then, it is still above 100 now). Sentiment in the industrial and construction sectors shifted from slightly positive to negative, with a much sharper decline in construction. This is reflected in official data – the value of construction works in Q1 2025 fell by 1.4% in current prices and 5.6% in constant prices. Meanwhile, sentiment in retail remains relatively stable and positive, though negative consumer sentiment has somewhat deepened. The decline in Serbia’s sentiment occurs in the context of broader European stagnation – sentiment in the EU27 remains slightly negative and largely unchanged despite falling interest rates, while in Germany, our most important trading partner, which ended 2024 with a decline in economic activity, sentiment is at one of its lowest levels since the pandemic.

Protests were certainly not the main culprit for the slowdown in economic growth in the first quarter of this year, but they exposed the fact that Serbia’s economic growth in recent years has rested on increasingly fragile foundations. It is normal for economic growth in a country to slow when public investments fall by 8%. But it is not normal for public investments to fall because, in the words of President Aleksandar Vučić, “there isn’t a damn soul who will sign any paper.” In fact, it was never normal that “damned souls” in Serbia signed papers at all – they did so because the President urged and pushed them through parallel channels of power built precisely to bypass institutions.

The infrastructure built this way has begun to crumble, as have the foundations on which such growth was based. The easy wins offered by Serbia’s eroded economic potential during the transition have been exhausted. Irresponsible construction, we hope, will no longer be tolerated by Serbia’s engineers. For further sustainable growth, and especially development, institutions must enable legal certainty and productivity growth by listening to the needs of the economy.

This primarily involves eliminating discrimination against domestic businesses, measures to support their investments and modernization (digitalization and alignment with green transition requirements), and ensuring increasingly better and more relevant educational profiles – essential steps to replace investors who are now leaving with those who need knowledge and skills.

None of this is on the horizon.

Read the article further exploring this topic HERE.

Sustainable and resilient communities start locally

At the closing conference of the “Sustainable development for all” project, held on April 4 in Belgrade, CEVES organized a panel discussion titled “Planning the development of sustainable, inclusive, and resilient communities.” Participants from various sectors – local governments, development agencies, and civil society – highlighted the key role of local actors in achieving sustainable development goals.

The discussion shed light on the barriers communities face in a centralized system – such as lack of autonomy, limited capacities, and poor communication with local economy – but also pointed to the potential of inter-municipal cooperation and good practices, such as the “Green-blue communities” project and CEVES’ SME100 initiative, which demonstrate how concrete policies can be developed from the ground up, empowering local businesses and fostering dialogue with the community.

The panel’s conclusion was clear: genuine sustainable development requires meaningful decentralization and systemic support for local initiatives.

SMEs in the focus of sustainable development at the Green Peak Festival

CEVES was a partner of the first Belgrade edition of the Green Peak Festival – Austria’s largest conference dedicated to sustainability – held on April 3. As a long-time advocate for the importance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) for sustainable and inclusive growth, CEVES premiered a short film showcasing the best examples of innovative and successful Serbian SMEs. The film was designed to highlight their contribution to sustainability and business resilience and is available HERE.

During the conference, CEVES’ president and director, Kori Udovički, participated in a panel discussion created, organized, and moderated by Sonja Avlijaš from the Faculty of Economics at the University of Belgrade, titled “Rethinking innovation: The role of SMEs in business sustainability.” Kori Udovički emphasized that Serbian SMEs, especially exporters, are deeply rooted in their local communities and highly innovative, as this is the only way they can survive, a view shared by the other panelists.

CEVES at the panel on Serbia’s development challenges

Organized by The Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, the World Bank, and CEVES, a panel discussion titled “Is Serbia trapped in the middle-income trap?” was held to present the World Bank’s report Greater heights: Growing to high income in Europe and Central Asia.

The key findings were presented by Dr. Ivailo Izvorski, Chief Economist for Europe and Central Asia at the World Bank, with participation from academic Pavle Petrović, Dr. Milojko Arsić, Dr. Kori Udovički, and Dr. Nicola Pontara.

The panelists agreed that domestic private investments remain low, and Serbia’s growth continues to rely on foreign investments and public consumption.

CEVES particularly highlighted that Serbian SMEs rarely grow into large companies – despite examples like SME100 showing high potential for innovation, exports, and growth. For these companies to become the backbone of sustainable development, deeper institutional and policy reforms are needed to support their growth beyond the SME framework.

The report is available at: Greater heights: Growing to high income in Europe and Central Asia.

Is Serbian economy suffering from Dutch disease?

An introduction to the analysis of the need for a new economic policy

In early June 2025, CEVES will organize a roundtable with leading economic experts in Serbia to open an evidence-based discussion on whether the Serbian economy could be diagnosed with a specific form of Dutch disease. This will be the first in a series of roundtables aimed at recommending economic reforms and policies to enhance Serbia’s competitiveness, supporting citizens striving for the establishment of the rule of law and accountable institutions.

Partnerships and cooperation for development

CEVES has started a new project with the International Labour Organization (ILO) to explore how climate change affects employment in Serbia and identify policies that promote a just transition to green jobs.

CEVES has also begun a market assessment for factoring in the Western Balkans for the International Finance Corporation (IFC), aiming to identify barriers and opportunities for developing this financial instrument to support the growth of small and medium enterprises in the region.

Thank you for following our work and contributing to the dialogue on sustainable and just development in Serbia!

Your CEVES team

(SR) Srpska privreda: Zverka kojoj je vreme da riče

(SR) Transparentnost, obim i ciljano usmeravanje državne pomoći na Zapadnom Balkanu: Ključ za rast?

(SR) Bilten: Studenti su u pravu; ekonomsko stanje Srbije, EU

(SR) Novi izveštaj Platforme „Održivi razvoj za sve“: Da li je cilj na vidiku?

(SR) MSP su i centar i margina: poreski kredit važi za velike, ali ne i za male firme

(SR) Predlog budžeta za 2025. godinu – javne investicije bez dugoročnog plana i razvojnih prioriteta, podrška privredi inertna

(SR) Subvencije idu strancima, poreska politika ne ide naruku MSP-u, a nešto je i do samih preduzeća

(SR) Kongres neće odobriti ogromno rezanje budžeta koje Mask najavljuje

(SR) Prozjumeri – neiskorišćen mehanizam u Srbiji

(SR) Panel diskusija: Prozjumeri i energetska sigurnost u Srbiji

SME100 Expo 2024: A New Growth Agenda for SMEs

SME100 Expo 2024, held on October 18, 2024, in Čačak, under the slogan ‘A New Growth Agenda for SMEs’ brought together 350 participants, including over 100 leading domestic small and medium enterprises, representatives from more than 20 key national and international institutions, as well as numerous members of the financial sector, aiming to further improve the business environment for Serbian SMEs.

The event, organized by CEVES and the Čačak Science and Technology Park, showcased successful family-owned businesses that make significant contributions to their communities. Panels covered topics from overcoming market challenges to accessing financial support, emphasizing SMEs as key economic drivers in Serbia.

With exhibitions, panel discussions, hard-talk sessions, and awards for the Super Champions — the best among Serbia’s top small and medium enterprises — SME100 Expo, for the third consecutive year, confirmed the growth potential and resilience of Serbia’s SME sector in an ever-changing global economy, while also reminding policymakers of initiatives that could enable even faster and stronger growth in this sector.

Find conclusions and a brief overview of the event here.

(SR) MSP sektor u Srbiji 2024: Analiza stanja i pregled MSP100 inicijativa

(SR) Koraci ka intenzivnijoj razvojnoj podršci MSP sektoru u Srbiji

(SR) Struktura cena i moguća rešenja za domaće tržište – poreska politika, troškovi distribucije i ulazne cene su ključni

(SR) Medić: Investicioni kreditni rejting smanjuje trošak zaduživanja

(SR) Pavle Medić o „Najboljoj ceni“: Takva vrsta politike nije moguća dugoročno, cene u Srbiji su slične cenama u EU, a plate dva i po puta niže

(SR) Nuklearna energija energetski najefikasnija, ali za „proizvodnju“ kadrova potrebno i do 20 godina

(SR) Zapadni Balkan manje energetski efikasan od EU zbog niske cene struje i više decenija nedovoljnih investicija

(SR) Potencijal za sigurnost energetskog snabdevanja kroz promociju prozjumerskog tržišta

(SR) Predstavljen MSP Kompas–rezultati u 2023. i očekivanja u 2024.

(SR) Smanjivanje administrativnog jaza i stavovi privrede o Inicijativi Otvoreni Balkan

SME COMPASS INDEX 2024: SMALL BUSINESS – GREAT POTENTIAL, Friday, May 17, from 11 AM, Chamber of Commerce of Serbia, Resavska 13-15.

(SR) CEVES Bilten – mart 2024

(SR) Novi Plan rasta za Zapadni Balkan – stidljivim koracima ka (evropskoj) budućnosti

(SR) Nemačka ključna destinacija za srpska mala i srednja preduzeća

(SR) Poreski kredit bi za pet godina povećao investicije za 40 odsto

(SR) Nova Vlada Republike Srbije da se fokusira na pravi plan razvoja: održiv i namenjen svim građanima i privredi Srbije (naročito MSP)

(SR) Vraćanje poreskog kredita najbitnija stvar koju država može da uradi za MSP

(SR) Zašto Srbija ima tako puno stranih, a tako malo domaćih investicija?

(SR) Među desetinama hiljada domaćih firmi samo njih 500 izveze robu za više od četiri miliona evra

(SR) Novi marketinški trik aktuelne vlasti: “Srbija 2027” eldorado iz šešira

(SR) Kvantni skok od tri odsto: Ekonomski efekti projekta Jadar

(SR) Pozitivan sentiment MSP za narednih pet godina ne prate planovi za investicije

(SR) Ceves opservatorija

(SR) Pohlepa zgodan osumnjičeni za visoku inflaciju

(SR) Dogovor između trgovaca i države nema potencijal da slomi inflatorna očekivanja

(SR) Održana Letnja škola „Zelena tranzicija i digitalna transformacija“ za sledeću generaciju lidera domaćeg MSP sektora

(SR) Osvrt na ekonomsku i monetarnu politiku Srbije: Izveštaj sa sednice radne grupe Nacionalnog konventa o Evropskoj uniji održane 29.8.2023. godine

(SR) Kamatne stope nisu glavni uzrok niskih privatnih investicija

(SR) Marijana Radovanović za NIN: SRPSKA PRIVREDA IZMEĐU VELIKIH DRŽAVNIH I MALIH I SREDNjIH PRIVATNIH PREDUZEĆA – U raljama neefikasnog državnog kapitala

Conference Enhancing Local Economic Development Planning through Inter-Municipal Cooperation held in Niš

On Tuesday, July 11, 2023, the conference “Enhancing Local Economic Development Planning through Inter-Municipal Cooperation” took place in Niš, organized by the Center for Advanced Economic Studies (CEVES) in collaboration with the Regional Development Agency South. It was the first out of three events that will be organized by the “SDGs for All” Platform with aim to initiate the exchange of experiences and knowledge among municipalities and cities throughout Serbia about the localization of SDGs and their integration into local planning documents. The event assembled representatives from the local self-governments of Nišava, Pirot, Zaječar, Toplica and Jablanica districts, as well as central-level institutions, development projects, civil society organizations, and agencies.

The conference began with a presentation of the results of a questionnaire concerning the organizational and functional capacities of local self-governments in four districts of South and East Serbia, essential for the development planning process. The presentation was conducted by Tatijana Pavlović Križanić, expert in local economic development. The recommendations derived from the questionnaire’s responses focused on improving the sustainability of the planning system, enhancing inter-municipal collaboration, and fostering cooperation with the private sector and civil society organizations.

The first panel addressed the state of development planning in the local self-governments in line with the principles of the 2030 Agenda. Panelists included Anja Stančić, a senior advisor in the Cabinet of the Minister for European Integration; Sanja Mešanović, Deputy Director of the Public Policy Secretariat; Milena Radomirović, Director for the Planning System and Public Finances at the Standing Conference of Towns and Municipalities; Marija Đošić, Head of the Local Economic Development Office in the City Administration of Pirot, and Nataša Vučković, General Secretary of the “Center for Democracy” Foundation. The panelists agreed that further efforts are needed to strengthen the capacity of local self-governments in creating and implementing planning documents, standardizing these processes, prioritizing objectives in planning documents, and ensuring predictable funding for local self-governments.

The second panel focused on showcasing examples of good and/or alternative practices in sustainable development planning. Among the panelists were Dragana Stojanović, Director of the Regional Development Agency South; Viktor Veljović, Manager of the EU Pro Plus Capacity Development Sector; Ivan Pavlović, Head of the Development Planning and Project Management Sector at LEDO Niš; Dragan Mančev, a member of the Municipal Council for Economy and Agriculture in Dimitrovgrad; and Luka Milovanović, Program Assistant at the BFPE Foundation for Responsible Society. During the panel, the RDA South presented the initiative to form regional councils that would actively collaborate with local self-governments. These councils, focusing on business and investment, infrastructure, agriculture and rural development, as well as social development, should provide concrete assistance to local self-governments by identifying common issues and developing initiatives addressed to decision-makers and donors that contribute to the joint development of local communities. The panel emphasized the significance of a participatory approach in defining territorial and local community priorities, as well as the importance of considering the realistic capabilities of local self-governments and utilizing the existing knowledge and capacities of development organizations and other stakeholders in sustainable local development.

Based on the discussions held during the conference, CEVES will prepare a document containing conclusions and recommendations that will define further work on enhancing local economic development planning. The document will serve as a foundation for future inter-municipal exchange events within the “SDGs for All” Platform.

CEVES joins the Global Forum for National SDG Advisory Bodies on behalf of the “SDGs for All” Platform

On behalf of the “SDGs for All” Platform, in June 2023, CEVES joined the prestigious Global Forum for National SDG Advisory Bodies. The Global Forum is a network that connects the knowledge and experience of multi-stakeholder advisory commissions, councils and similar bodies for sustainable development. These bodies contribute to the national institutional architectures for the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). By bridging knowledge and interests of various stakeholder groups, multi-stakeholder advisory bodies foster social acceptance and cohesion within society in times of transformation.

As a member of the Global Forum for National SDG Advisory Bodies, CEVES will actively participate, on behalf of the “SDGs for All” Platform, in international discussions and knowledge exchange on sustainable development, sharing contributions developed within the Platform, as well as acquired experiences and lessons learned. Membership provides an opportunity for Serbia to exchange experiences, best practices, and lessons learned with other countries, enhancing global collaboration and collective efforts towards achieving SDGs.

The “SDGs for All” Platform will leverage its membership in the Global Forum, as well as the knowledge gained within it, to continue advocating for policy coherence and effective implementation of the SDGs at the national level. By joining the Global Forum, the “SDGs for All” Platform reaffirms its commitment to sustainable development, fostering collaboration, and guiding Serbia towards achieving SDGs, thus strengthening its position as a key player in driving sustainable development efforts in Serbia. We expect that these partnerships will accelerate efforts in building a better future for all, leaving no one behind in the pursuit of a more sustainable and equitable world.

(SR) Održivi razvoj: jačanje kapaciteta poslovnog sektora – radionice u tri grada u Srbiji

(SR) Podneta inicijativa za izvoznu podršku MSP šampionima

(SR) Ivanović: Raste izvoz u Rusiju, domaće firme koriste globalnu situaciju

(SR) Šormaz: Poslovno okruženje u Srbiji povoljnije za velike strane firme nego za domaća MSP

(SR) Izveštaj: Skrining Inicijative Otvoreni Balkan – analiza po zemljama

NEW DATE MARCH 2nd: It’s time for SMEs!

In cooperation with the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Serbia, CEVES is organizing the event (panel discussion and exhibition) “It’s time for SMEs!” on March 2nd at 9.30-12.15 at the premises of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Serbia, Resavska 15, Belgrade.

The panel discussion on the importance of SMEs and what is needed for this part of the economy to continue to grow and contribute even more strongly to the sustainable development of Serbia will be followed by an exhibition of the selected companies, representatives of the SME100. The companies are selected according to the clearly defined export criteria, their contribution to the development of local communities, innovations in business, commitment to green business and contribution to the sustainable development. Profiles of these companies are available here.

The program includes a short presentation on the importance of SMEs and a panel with representatives of the SME 100, state institutions important for the development of SME sector, Serbian Chamber of Commerce and Industry and experts for the SME sector. You can find the preliminary program here.

The Conference is organized within the “SDG For All” Platform, supported by the Governments of Switzerland and Germany and implemented by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH through the Public Finance Reform – 2030 Agenda project.

Participation is free of charge, with mandatory registration here. After the panel, light food and beverage will be served.

Gostovanje u Dnevniku – Kori Udovički 30.12.2022

Gostujući u Dnevniku, Kori Udovički komentarisala je godinu iza nas. Kako je ekonomska i energetska kriza uticala na Srbiju i Evropu, da li je Srbija zaista otpornija nego druge zemlje na ovakve šokove, o aranžmanu sa MMF, situaciji u EPS-u i drugim temama možete poslušati na sledećem linku.

USAID – Big small economy

Analysis of Serbia machinery and equipment sector with map of fimrs

Economic sentiment and confidence indicators

Index of economic mood and its components by countries of the region

Both the businesses and consumers see that the zenith of Serbia’s ongoing economic recovery is behind us—from the position of the best “economic mood” in the region, which it held during the pandemic until July 2021, Serbia falls to the second lowest mood (after the most affected North Macedonia), especially since January.

Serbia was one of the countries that took the lead in the post-pandemic recovery, but also a country where the decline in economic sentiment began even before the war in Ukraine

Perceptions of the sectors moved in opposite directions, where the sales and service sectors managed to maintain a relatively high level, while the industry, construction and consumer “sector” experienced a sharper decline. Even if the consumer sentiment managed to remain at an enviable level throughout the corona period, it started to decline sharply from July 2021 and reached the level of -6.8%, which is its lowest value since September 2017. The sentiment in the industry and construction sectors sharply began to decline with the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine. The development of events in these two sectors can be connected with the sudden increase in the prices of energy, construction, and raw materials, as well as with problems in supply chains. Both sectors contribute negatively to the economic mood and are at the level of -2% and -7%, respectively. Three sectors with a negative sign indicate that more than half of the economy perceives the current situation as worse than usual. On the other hand, sentiment in the sales and service sectors managed to remain at a high level of 8.7 and 10.8%, respectively, and thus contributed positively to the composite index of economic sentiment in Serbia.

The index is currently at the level of 96.10%, which is the lowest value since the end of 2020.

The situation in other countries can be viewed in the chart below by selecting the country you are interested in, and for details click here.

Green energy for our children (for real)

Author: dr Kori Udovički

In Serbia worries about the energy crisis are fading. However what remains is the mistaken idea that green energy is to blame. Even worse is the notion that it is good for Serbia not to give up its coal. In Serbia, only a few weeks before the Global Summit in Glasgow there had not been a single mention of the Summit. It is true that some of the recently adopted green European polices have contributed to an additional jump in energy prices, but the causes of the crisis lie elsewhere. One cause is the unpredictability of supply and demand not only in terms of energy but within the context of the global recovery from the crisis brought about by the pandemic, especially in the case of China. Another is the intensified manifestation of climate change that can only be dealt with by focusing on green energy. Still, even if it were true that green policies are to be blamed, it would be a big mistake to cheer having ignored this problem for so long. The last train is leaving for humanity to be able to contain climate warming to somewhere between 1.5 – 2.0 C – the limit beyond which our life on earth would become unimaginable. In the event we miss the train Jeff Bezos is “getting ready for Mars”. But where will Serbia go?

The pandemic and the unstoppable growth of Chinese demand

During last year’s lockdown, fossil fuel prices plummeted– to the point of the price of oil even turning negative! Just as then this could not be blamed on the slow global transition to green energy sources, now a presumable rush in that direction should not be blamed for their dizzying growth. This time, the difficulties in forecasting the demand for everything, including energy, were followed by unexpected, record high, growth of China’s demand for thermal energy (gas, coal, nuclear energy). In the 12 months to August, Chinese consumption went up by as much as 14 percent compared to the previous period, although economic growth was relatively slow. The Chinese demand for gas was increasing even faster, not because China had given up coal, but because its record-breaking production has been growing more slowly. Coal production would have gone up more if coal-mine safety standards had not been strengthened following a series of accidents leading to loss of life for the miners.

China has not (yet) phased out coal, nor is it cutting down its production. For now it is only (reasonably and understandably) trying to meet its voracious growth in energy demand by increasing the share of renewables and the much slower growth of coal consumption. There is no doubt that China has embarked on a path of renewables because of its well-known long-term view of the future. The pollution of Chinese cities has provided an additional sense of urgency. It is also obvious that in this particular case, the problem lies primarily in the imbalance in the Chinese energy market, to which the Chinese authorities have responded in the only way possible at present: by raising the price of electricity for industry and quietly announcing a price increase for households as well.

Extreme climate and geostrategy

Meanwhile, throughout the past year global warming brought about an extraordinary number of examples of extreme climate events affecting the rise in demand and a drop in fuel production. First, the winter was extremely cold and the summer was extremely hot, thus causing a rise in energy consumption, gas especially, for heating in the winter and for cooling in the summer. At the same time, due to extreme rainfall and floods coal production declined in Indonesia and Columbia, the key global market suppliers, whereas drought (yes, you guessed it–extreme again) in Brazil reduced the Brazilian production of hydro-energy and drastically increased their demand for coal and gas on global markets. All of this was followed by declining wind farm production in the North Sea due to unusually mild winds.

Here we need only briefly mention geostrategic factors as they are not the focus of this text. It is quite certain that Russia was somewhat hesitant about supplying gas hoping that this would bring forward the launching of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline. At the same time, the sanctions imposed by China on imports of Australian coal (which are now being quietly bypassed) contributed to China’s problems.

We can only wish the problems derived from the accelerated transition to green energy! To the contrary, global greenhouse emissions stand at record-high levels. An accelerated construction of renewables facilities is the only possible long-term response to this crisis, and even beyond, to the climate crisis. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has estimated that the current construction effort by the global public sector is currently three times lower than required to keep the global warming below the desired limit. Luckily, the EU response to the ongoing crisis is to announce higher investments in energy transition. Still, it is questionable whether the current crisis will weaken the measures the world would be ready to commit to in Glasgow. These measures need to finally and effectively change the ways in which we are living today.

Fallacy instead of clarification

In this regard (and in many others), Serbia is persistently being fed a red herring.

“Coal ensures our energy independence.” And why would it be a problem to “independently” rely on our own renewable energy? By relying exclusively on coal, we can secure demand for the next 30 years, while entering into conflict and showing no solidarity, with the accountable world and our offspring. By relying on renewable resources, Serbia can secure its “independence” for the centuries to come, given that Serbia is abundantly endowed (despite still not having a fair estimate of just how much and at which cost). Just to make this clear, for the time being, “relying on renewable sources” surely implies a necessary reliance on thermal energy for the so called “baseline production”. “With coal we can sell electricity when the price is high and buy it when it’s cheap.” We can do the same if we start gradually phasing out coal and switching to renewables.

True energy independence is a privilege of a small number of countries, and Serbia is surely not one of them. However, even such countries, not only the US, but for instance Saudi Arabia as well, have started heavily investing in renewables. It is a fact that renewable energy calls for intensified trade in energy, and, in our case, this means deeper integration with the European energy market. Relying on gas, highlighted these days as a positive trait, and let alone oil, will not bring energy independence either. I am not convinced we are getting gas at an extremely favorable price, but if that were true, this would only corroborate the non-existence of independence. Nothing comes for free in economics and politics.

The actual reason underlying the resistance to green energy in Serbia is the political economy. One of the aspects is that (for now) it unquestionably costs more than coal-based energy. The other is that coal is linked to a whole range of strong, even corrupted, vested interests. All these are difficult factors for a populist government to handle. Still, they are not insurmountable – we just need to take into account the fact that the price of fossil energy should include the cost of our health and the cost of corruption.

The responsibility of “common” citizens

An essential issue remains – accountability. It can be debated how big should the contribution of “small and poor” Serbia be in fighting climate change. However, we cannot simply ignore this fight. It would be irresponsible, and also wrong, to lull ourselves in the notion that the green transition is something imposed on us by the “evil West”. Quite contrary to that, the strongest pressure for action was created by green parties protesting for years against global capital and the powerholders. For years, these were not mainstream forces. The facts about climate change have been persistently stressed by the United Nations panel convened three decades ago, comprising nowadays more than 600 of the most eminent global experts

The most affected by climate change are actually the poorest- small poor island countries that will, for instance, be entirely flooded, or tortured semi-desert-based agriculture that will become completely thwarted.

The awareness about the necessity for change penetrated the mainstream in full force with the adoption of the UN 2030 Agenda, namely of the Sustainable Development Goals back in 2015. Serbia, however, is still ignoring them. Luckily for our grandchildren, “ordinary” Westerners are becoming increasingly engaged, and the awareness is now reaching more and more people in power. This May, in a single regular day, an “ordinary” judge in the Netherlands had ruled that the Royal Dutch Shell company ought to reduce their net emissions by 45% by 2030. At the same time, a small, so called “activist” hedge fund “Engine No 1“ won in the fight for a similar change in the policy of ExxonMobil, the largest oil company in the USA. The Fund achieved this by engaging in raising the awareness of the major shareholders- these are the pension funds of “ordinary” people- to vote in favor of a change at the company assembly session. On the same day, the shareholders of Chevron, the second largest US company, voted for the emission reduction. It doesn’t matter anymore if the vote of the shareholders is cast this way because of the future of their own children or because it feels stupid to hold the shares of a company not accepting the fact that the demand for their products is declining, so it may as well disappear one day. What matters is that the change is not doubted any longer.

I made a joke at the beginning of this text. The richest man in the world, the owner of Amazon, Jeff Bezos, recently took his first cosmic flight in his private rocket: he didn’t say he was planning to flee to Mars, but that, in his view, mankind will have to move their polluting production “somewhere out there”. I truly believe this will not be needed. In any case, Serbia cannot and should not try to remain “independent”, while actually being isolated and poor. The green transition is leading us to the future. It would be much better to steer this journey on our own, in a smart and accountable way, using our own potential, than to be forced to do so while lagging behind the others.

The economy or the nation’s health – a false dilemma

Currently, the text is available only in Serbian.

Working Group of the National Convention on the European Union for Chapter 32 – Financial Control, coordinated by CEVES, held a meeting with the Central Harmonisation Unit

Working Group of the National Convention on the European Union for Chapter 32 – Financial Control, coordinated by CEVES, held a meeting with the Central Harmonisation Unit on 11.03.2021. For the minutes from the meeting click on the link.

Positions of the Working Group of the National Convention on the European Union on Chapter 17 – Economic and Monetary Policy

CEVES held a meeting of the Working Group of the National Convention on the European Union on Chapter 17 – Economic and Monetary Policy on 11.03.2021. The position of the working group is that, although Serbia has achieved notable macroeconomic performance, there has been a growing macroeconomic imbalance, a lack of progress in strengthening the country’s capacity, and an intention to pursue complex economic policies needed to address the underlying structural factors. We thank the members of the working groups for their expert contribution, the National Convention on the European Union, and the European Commission for the opportunity to express our views, and we look forward to future cooperation. Click on the link for more details.

The Price of a Cynical Electoral Calculation

Thisi is a slightly edited version of the article published in NIN magazine on July 30th, 2020.

Author: dr Kori Udovički

At a time when officially hundreds, and possibly many more, people are dying from covid in Serbia, it is important to be quite clear that this was not inevitable. It is not true that in this crisis one has to choose between the health of citizens and the economy. On the contrary– health management has become one of the most important economic policy tools – if the government does not keep the epidemic under control, its explosive spread takes control of everything, no matter how much the government resorts to repression. People in Serbia are dying today because of a cynical electoral calculation, but also because Aleksandar Vučić– despite holding a tight grip over his party and the (repressive) state apparatus– is not able to manage the fine web of measures and incentives needed to take the Serbian economy to safety. Had he been able to, he could have won the election with greater political gain and benefit for the economy, without the unnecessary loss of life.

The first and second waves

Every day of this second wave of the pandemic is costing the Serbian economy over a million and a half euros in earnings—a rough and conservative estimate– compared with what could realistically have been expected after the state of emergency. It was to be expected that, at least for a year from now, businesses would operate under the twin effect of the restrictions’ direct limitations, as well as of the contraction in demand caused only partly by the restrictions themselves, but more so by the broader effects of the crisis in Serbia and internationally. The estimate of the additional cost includes the effect of the current deterioration in both these factors. Not included are the increased costs of health treatment (which will ultimately also be paid by businesses) and the chain effects of increased uncertainty and of failures of the most affected businesses.

In order to understand this wave, as well as how the epidemic can be better managed, it is useful to look at what can be learned from the state of emergency—although it is quite safe to assume this will not be exactly repeated. It should not repeat because everybody – businesses, citizens, and the government—have in good measure become adapted to the inevitable new circumstances.

As with the first wave, this one is most strongly affecting micro, small, and medium sized limited liability companies and sole-proprietors (SMEs) – those that make the heart of the domestic economy.

The chain of causality during the state of emergency started with the closure of those activities that require direct contact or the gathering of large numbers of people (hotels, restaurants, personal care, open and enclosed market places). CEVES’ research shows that every fifth limited liability company (LLC) mainly micro, and every third sole-proprietor (with a total of some 230,000 formally employed) were not able to operate at all. In addition to businesses closed outright by the measures, also blocked were workers older than 65 and those that were not able to organize transport for their employees. However, for the majority of businesses, the first wave was centered around the need to adapt to safer working conditions. Establishing physical distance, working in staggered shifts, the use of PPE and disinfectants, shifting to digital/remote work in whatever capacity possible- all of that entailed costs that continue to burden businesses.

For the two thirds of SMEs that could not (partially or fully) shift to remote work, shortened work hours were highly limiting. Retail outlets were hit particularly hard, not only by the shortened work hours, but the many days of forced holiday. Difficulties with, and the increased costs of, procurement and transportation of inputs should be added –problems which continue to be felt, especially in the import and export of goods.

Once operations were adjusted, the main cause of SMEs’ loss of income was the fall in demand. During the state of emergency, 40% of SMEs lost over 50% in profits; only every fourth LLC and every fifth entrepreneur had profits in line with pre-epidemic expectations. As soon as the state of emergency was ended, some businesses had even higher demand than usual (e.g. hair salons), while others dealt with continued shortfalls. Some sectors, especially those related with tourism, faced an especially drastic decline- in May, Serbia had 87.6% less tourists than at the same time last year. It was realistic to expect a continued shortfall in demand in other exposed sectors as well, considering that the public needed to be continually reminded of safety measures. Some niches (eg. international congress tourism) would clearly not find solutions for the medium-term on their own. Instead, in June and July, the neglect of strict safety measures and a “we beat corona” attitude took hospitality and other similar businesses to a surprisingly high level.

Their decline is now that much more severe, more so due to the fall in demand and caution by citizens than restrictions. Coming out of the state of emergency, SMEs were optimistic. Covid caught them in the first rush of economic growth since the last crisis. According to CEVES’ research, they had in the meantime significantly increased exports and their contribution to the Serbian economy. They had even built up reserves– during the state of emergency, only 1% of SMEs let go of employees.

Elan and reserves

The first set of economic measures served to replenish part of the reserves that SMEs spent during the state of emergency. As such it was justified and its lateness (in contrast to my previously stated expectations) was less important. About two thirds of businesses resorted to deferring tax debts (the moratorium on loans was used by much fewer of them, because few SMEs borrow at all). Additionally, two thirds of businesses stated that they relied on their own reserves and the help of family and friends in order to aide their financial problems during the state of emergency, while 90% took (or were simply given) the minimum wage subsidy. Still, surveys showed only 5-10% of them reported that the government measures influenced their decision to (not) lay-off employees. About one fourth said they didn’t even have issues with making payments.

The greatest price of the new wave lies in the collapse of that optimism and the aimless depletion of those reserves. It takes the courage or ambition of many entrepreneurs to secure sustainable economic growth– and it requires that they believe it makes sense to risk their assets and savings. The crisis is not an opportunity as such, but crisis or not, the chances and ability of every entrepreneur to uncover solutions, to invest their reserves in the small opportunities they see – must be protected. This is possible only with consistent, predictable, and, if possible, agreed upon economic policies. In their absence, discouragement and costly directionless searching take over. Although the delay of the first set of measures did not in itself create a problem, it is a reflection of a deep problem that is yet to take its toll. First of all, let’s clear up the myth that the first set of measures had to be so broadly targeted and expensive due to the speed and limited administrative capacity of the Serbian state. All the countries that Serbia compares itself with adopted the first set of measures in the third or fourth week of March. Serbia announced a set on March 31st, and it adopted it only on April 10th. Additionally, all the countries in the region, and many others outside it, had much more targeted sets of measures.

One instead of all

The question is why was the set of measures late? I have no doubt that it waited on the “de facto” Minister of Finance to stop doing the job of the “de facto” Minister of Health. The public is very familiar with the effort Aleksandar Vučić personally put in to control the health aspects of the epidemic during the first month of the crisis: from selecting the professional advice to rely on, through the procurement of respirators while playing geostrategic policy, to the role of a spokesman for the Crisis Task Force. In the meantime, the economy and economic line ministries were preparing proposals that were waiting for a response. The first economic messages he sent into the ether were related to maintaining salaries in the public sector, supplementing pensions, and giving raises to health workers. Most likely, he was only able to pay attention to the economy when new health policies were following advice from the Chinese physicians (at the beginning of the last week of March). Meanwhile, only the National Bank appears to have acted autonomously.

The biggest problem in all of this is not the tardiness of important decisions (e.g. currently—forming the new Government). Even the disenfranchisement of ministry leaderships is not an insurmountable problem – Vučić can replace more than half the ministers (the policy of mass testing adopted near the end of March was in fact correct). The problem is that the occasional benefit from such engagement cannot even remotely compensate for the damage done by the unpredictability and caprice of such decision-making at the highest level. It disempowers and paralyzes entire ministry realms, from top to bottom. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that it is accompanied by a subtle, yet effective, message that nothing is to be expected from the initiative of the small individual, within the government and outside it. There is no hint even of a message that joint action, mutual help, but also a free (and fair) competition of many small and big players in society can create something valuable for the whole society.

When we look at how other countries adopt measures, it is obvious that they work in parallel tracks. Measures spring up in waves: first one minister, then another is announcing a step, there is a public dialogue – some of it nationwide, some between ministries and their constituencies. Businesses are investing in adapting to the new situation by connecting their interests and the health of citizens in ways that only they could have thought of – digitalization, better ventilation, new procedures that protect both employees and clients. The governments, with detailed sanitary analyses and instructions, support and follow the initiatives.

Do not get me wrong: business people in Serbia are fighting hard, and individuals and institutions everywhere, even within the government, are working as hard as they can to adjust their activities and make them as useful as possible in this moment. During the crisis, the Chamber of Commerce stood out with its engagement and agility. But that is not the same as mobilizing entire ministry realms into coordinated action top-down and bottom-up. The first set of measures should have been understood as buying time – to prepare the economy and the state for the “new normal”.

A chip off the old block

The set of measures did buy time, but — what for? The clarification did not follow. Immediately after coming out of the state of emergency, many businessmen probably had unrealistic expectations. Less than five percent thought they would need any debt forgiveness to survive! Only later in June did the realization begin to set in that serious problems await for the medium term. Like anywhere, the business sector needed political leadership: the “de facto” prime minister initiating and supporting a nation-, or at least government-, wide dialogue about what this “new normal” will look like- how much will it cost, what expectations could no longer be realistic? Hardly anyone reading the international press could have doubted that the hospitality sector, and especially hotels focused on international tourism, would remain under unbearable pressure. What is the country’s policy for them five months after the outbreak of the crisis?

In this unprecedented crisis, no one has the crystal ball (or time) to work out ambitious policies and strategies. But it is possible and necessary to clearly weigh what portion of the country’s resources will be allocated to civic solidarity, and what to investments that we believe can pull everyone ahead? What principles do we stand for as a nation? One must, for example, choose between the following two: “unless something much worse than expected happens, we will not allow the country to be left without these, or such and such, hotels” or “we do not believe that even in a crisis like this, hotels should be helped. Some will fail, some who still have the resources will buy them.” With or without a national dialogue – which of the two is Vučić’s position? Instead of answering these questions, more than two months after the adoption of the first set of economic measures, the announcement of the second begins, and it is just a chip off the old set’s block.

(SR) Komentar na usvojene i najavljene ekonomske mere za ublažavanje posledica Kovid-krize

An Imperative for Support Measures – Abundant Liquidity to Accompany Payment Discipline

By Kori Udovički, orig. 29/03/2020, rev. 01/04/2020

The pandemic struck us just at the very moment when the payment discipline in Serbia begun significantly to improve. The measures to strengthen financial discipline in the private sector adopted in 2016 and the reduction in government arrears in the context of the fiscal consolidation, significantly reduced the chains of illiquidity in the system. Of course, no one could expect the pandemic, and it will inevitably cost us. But if the payment discipline is now loosened, the pandemic will cost us much more. Clearly, those who cannot access liquidity will simply not be able to pay. It is the Government’s responsibility to make sure there are as few of those as possible. In this, it must start from itself.

If the Government wants to mitigate the economic downturn during a pandemic and ensure its rapid recovery once the pandemic is over – a key task is to accompany intervention measures with safeguarding payment discipline. I start by assuming that it is clear to the reader how important this discipline is to economic growth. In short: non-payment creates a chain of illiquidity, which then creates problems for everybody. The first debtor affects his partners, suppliers, and employees, who in turn pull those, now many, into the third line of iterations, and so on. In this way, illiquidity snowballs through the system, further affecting everyone – even those whose business otherwise would not have been affected by pandemic at all. Its worse aspect is that it tends to spread distrust, discouraging new business ventures, and this carries over into the post-crisis period. Simply, economic activity is stifled over the longer term.

Payment discipline is actually one of the pillars of financial discipline. We understand financial discipline as “you incur only those costs that you can afford to pay”. We mostly interpret this as having to plan one’s budget carefully – which is, certainly, its first pillar. However, the discipline of realistic planning does not make sense unless it is accompanied by payment discipline. Once a cost has been incurred –it must be paid for. Even if it requires borrowing to pay. Not even the best plans can predict everything. Liquidity needs to be available/accessible if prompt payment is to always be possible. So, access to liquidity can be considered the third pillar of financial discipline. These three pillars reinforce one another. We will really take care to plan realistically only if we know with certainty that we will have to pay. Only if we plan realistically, will we be creditworthy when we need to access liquidity when unexpected problems do happen. And, finally, only if we have access to liquidity, will we be able to act upon that creditworthiness, that is–to borrow and to pay.

Financial discipline is a matter of political will and upgrading of the financial management system. In the distant past, we planned unrealistically and borrowed without much consideration. In the end, we paid for it through inflation. In the 1990s we had both hyperinflation and non-payment. Since the 2000s, we have started to plan somewhat more realistically, but not sufficiently. Therefore, we continued to fall back on non-payment, the so-called arrears. The unpaid expenditures from this year burden next year’s budget and hence leave less space for next year’s spending. However, this means that instead of the financial market, the difference is financed by businesses and citizens. The key at this point is to understand how harmful is the non-payment culture, and to tackle it. The Government needs to dare to look for liquidity in the market to cover the difference between expenditures and revenues, even unexpected ones. For financial discipline to be maintained despite more flexible borrowing in the market, Serbia needs to use more decisively and honestly its financial management instruments: primarily budget planning and oversight, which have been built over the past two decades.

Controlling the level of spending by limiting payments, in a time when the state needs to stimulate economic activity by increasing the deficit, is like stepping on the gas of a car while pulling the parking brake. It is this odd combination of actions that explains why in 2010-13 large fiscal deficits did not contribute more to growth. By the same token, a combination only in opposite directions explains how the recent sharp fiscal consolidation of 2015-2017 was not accompanied by such a larger contraction in economic growth: the tightening of the fiscal belt was accompanied by a reduction in public sector arrears giving the economy a substantial liquidity relief. It would be inexcusable if we fall into using the same wrong combination of instruments again. We need a true fiscal stimulus: a fiscal deficit, ie. overall public spending, paid for by adequate liquidity.

The price of the fiscal package, as well as its allocation, will be less important than the need that it be accompanied by a clear intention to maintain a sound financial discipline and the measures to do so. This should by no means be taken as a call to abandon reasonable budget planning. The state must weigh a very significant, but feasible package of support to the economy and citizens. In this greatly uncertain context, it is likely to err, but it should err on the side of looseness rather than tightness. We are witnessing “the mother” of unimaginable, unexpected events. Responsible planning, the first pillar of financial discipline will be observed if the plans are as realistic as possible, and then are revised as frequently as needed. The government, businesses, and citizens should certainly expect to produce much less this year, and therefore to be able to consume much less.

If paid in liquidity, excessive spending will be punished by inflation, which then needs to be quickly corrected. However, in its early stages of acceleration inflation would get as much production rescued as possible. Some increase in inflation should be expected and allowed, (this is a supply contraction crisis). However, if inflation starts accelerating, beyond 5-7%, then it could and should be arrested with corrective measures—tightening of spending, not by running arrears. Loosening of financial discipline overall, would, of course, mean repeating the biggest mistake of the past. If accompanied by excessive liquidity, it would lead to hyper-inflation. If, as is more likely, accompanied by insufficient liquidity and non-payment it would drag us into a “swamp” of unfulfilled obligations, general illiquidity and insolvency as well as distrust, putting a break on the eventual recovery for the fourth time in three decades. This, clearly, would depress economic activity for a long time to come.

Focus on Payment Discipline

In order to support payment discipline throughout the system, the government must show commitment, set an example, and pay off all its outstanding obligations. These are still substantial. Until recently, the state was the key ingredient in the lack of payment discipline in Serbia. On the one hand, as by far the largest single buyer in the market (procurement of goods and services by the public sector amounts to about 20% of GDP), its non-payments were, and may still be, the first and the biggest link in chains of non-payment. On the other hand, it is the Government that, through its example and actions, sets the culture of (non) payment. It sets the culture by taking on (un)realistic obligations and then (not)paying them, as well as systematically enforcing discipline in the private sector. This applies to both obligations that the Government assumes itself, and to those it obliges others to enter. Say, for example, that the Government requires the corporate sector not to lay off employees. As we all know that many companies will not be able to pay them, if the Government would not provide the means for them to do it, then we would all know from the outset that the Government is counting with arrears. The culture of non-payment would start to spread.

Maintaining a steady flow of money into the economic system will require the state to cover the difference between planned and realized resources through borrowing on the financial markets (in these circumstances, ultimately, with the central bank “printing money”), and not as was the case so far, by running arrears. Only thus will it extinguish the fire of illiquidity instead of stoking it with non-payment. On the one hand, the deficit needs to be maintained at the desired level by strengthening budget discipline, i.e. through more realistic budget planning (and by revising plans when developments go in an unexpected direction). On the other hand, payments and / or injection of liquidity into the system must go smoothly. The “music has to keep going” while the government has to keep paying promptly for it.

Realistic budgeting requires a systematic, not just political, disciplining of the public sector. Politicians at the helm of the state, like all of their appointees as well as civil servants, should believe that they are to budget realistically and that their expenditures will be paid promptly. This requires the introduction of genuine professional ex-ante control of public budgets that will check the reality of planning. At first, politicians might think that they are at a loss because their discretionary influence on spending would be curtailed. However, they would soon discover that they can still steer spending through policies, while earning many points for successfully managing the crisis.

As far as the private sector is concerned, the discipline of payment suffices to enforce financial discipline. Until the culture is changed, payment discipline must be imposed, but it also has to be feasible. On the one hand, the prospect of enforced collection or bankruptcy, if credible, will force everyone to plan costs realistically and to pay for them. On the other hand, in situations just like the current one, the private sector needs to have access to enough liquidity to pay even when their plans will obviously have been missed.

Availability of Liquidity

Securing enough liquidity, the third pillar of financial discipline, in general is the responsibility of the central bank. In these circumstances, it will also require that NBS’s measures be strongly supported by the Government.

The NBS has already taken adequate earliest measures to ease the immediate pressure of debt servicing on the economy and citizens. As a first measure, a moratorium on debt payments was introduced. This has put pressure on banks’ liquidity that the NBS has eased using favorable monetary and foreign exchange operations. Subsequent measures should contribute to the activation of the financial sector in support of the economy, especially the most affected ones. The problems are twofold in a crisis situation like the current. First, banks will need stronger incentives, as well as guarantees, to dare to issue new loans to most of their clients. It should be expected that tomorrow’s package of measures lends support to short-term lending, with low, zero or even negative interest rates. Negative interest is a subsidy to a bank and / or even a business entity. In this case, it is not only about providing liquidity but also about financial assistance to the borrower. The package is likely to also include significant government guarantees for loans issued by banks during the crisis, especially to the hardest hit sectors.

However, the second problem is that the above classic package of measures, aimed at enhancing liquidity through the financial system will not be enough for Serbia because its financial sector does not reach far or deep enough. The financial markets are so-called “shallow”-reflected in the low ratio of total domestic credit to GDP. While in countries with developed financial markets it is common for it to be 90-140% of GDP, in Serbia it is around 50%. In the more advanced transition countries. it is generally above 70-75%. This means, on the one hand, that our businesses rely heavily on own-resources and would not be hit as quickly by the bank credit crunch as those in more financialized countries. However, for the same reasons, our economy’s ability to recover from the crisis will depend on these funds not being exhausted. A particular issue is that most businesses are farmers and SMEs. SMEs generate about 27% and farmers about 6% of GDP. About half of SMEs do not borrow from banks, and the majority of those who borrow do so rarely. Under these conditions, banks will not know them well enough to take the risk or lending now. To make the problem worse, banks require guarantees in personal property from small businesses. How many will be willing to risk their property? And how fair is it to require it under these circumstances?

Matters are made worse by the fact that Serbia does not have an extensive network of special institutions dedicated to supporting and financing SMEs, like other countries do. For example, Germany’s package of measures envisages that significant amounts of liquidity assistance (€ 750 billion) are pumped through separate networks—the regular financial system and the network of support institutions for SMEs.

The state should help the NBS with its own actions as well. It would be a good idea to expedite the payment of all the Government’s liabilities dragging through the courts, or waiting in line to be paid by the Treasury. We know less about the Government’s first actions, but I hope that at least it will continue to spend regularly and pay its obligations promptly so that its powerful demand and liquidity help mitigate the contraction of the economy – until targeted measures in the announced package become operational. Also, in the very short term, I expect the state to assist the system’s liquidity through segmented deferral of tax liabilities – at different rates for differently affected sectors and even for different sizes of businesses. A low interest rate would encourage those who still do not need the liquidity to pay them anyway. The Government’s support measures for businesses and citizens will also supply liquidity. Subsidies were already provided to pensioners, and the payment of subsidies per employee for SMEs, should also be considered, especially for those in the most affected sectors. This would reach a significant number of households.

Many countries in the world (and Slovenia among them) have announced the purchase of corporate bonds that are likely to target vulnerable sectors. There are no corporate bonds in Serbia, but the possibility to help corporations issue them and hence start the development of the market should be considered. In particular, the economic viability and operational feasibility of securitizing claims on certain segments of the corporate sector, especially SMEs, should be considered. For example, the administrative securitization of 30% of the economy’s claims on SMEs with certain characteristics (size, sector, previous business performance) should also be considered. These securities could be packaged and the banks could buy them using facilitated credit terms and guarantees from the state. After the crisis, banks could unpack the packages, collect claims, and trade those securities. Most likely, business would emerge to interested in dealing with the assessment of the value of these securities and willing to trade and collect on them. Unlike many other scenarios, the risk of such a liquidity injection would be split between banks and the state and its cost could be calculated in advance.

The Serbian economy will not emerge stronger from this crisis, as will not the economies of the rest of the world. However, if there is political will, and with the proverbial ability of Serbia’s society to rally action and improvise in response to adversity, Serbia can come out of this crisis with a significantly strengthened system of macroeconomic management. This would allow it to be among the faster, instead of the slowest recovering countries.

(SR) Uloga i efekti državne pomoći u privlačenju stranih direktnih investicija (SDI)

Call for Project Proposals

Centar za visoke ekonomske studije (CEVES) u okviru projekta „Korišćenje ciljeva održivog razvoja kao vodilja preusmeravanja istraživanja društvenih nauka: Pilot projekat“ objavljuje poziv za dostavljanje predloga projekata na temu: “Ka postizanju ciljeva održivog razvoja u Srbiji: Kako su povezani kvalitet poslova i ekonomska struktura?”. Projekat je podržao PERFORM (PERFORM je projekat Švajcarske agencije za razvoj i saradnju koji sprovode organizacija HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation i Univerzitet u Friburgu), i on je deo šireg „Pripremnog projekta platforme za društveni dijalog o ciljevima održivog razvoja u Srbiji“ podržanog od strane Švajcarske agencije za razvoj i saradnju.

CEVES poziva istraživačke organizacije, akademsku zajednicu i grupe istraživača da podnesu svoje predloge projekta u skladu sa objavljenim uslovima konkursa. Uslove konkursa, istraživačku temu i sve druge dodatne informacije možete pronaći u PDF fajlu na linku ispod.

Svoja pitanja vezana za konkurs možete uputiti elektronski na adresu office@ceves.org.rs najkasnije do 11. maja 2018. godine.

Predlozi projekata se podnose na engleskom jeziku i u elektronski na adresu: office@ceves.org.rs sa naslovom koji se odnosi na ovaj poziv. Rok za podnošenje predloga projekata je 25. maj 2018. do 12h.

SR

SR